Writing my own OS

Writing my own OS

As I learn more and more, I realize how little I actually know.

My curiosity accelerates faster than my learning does. In order to quell this thirst of “why and how” I am going back to the basics.

For this project I will be building my own simple operating system. After which I hope to build my own computer (from scratch) to run this OS on.

I will be calling it SOs.

The guide I will be following is

https://github.com/cfenollosa/os-tutorial

As I go along it, I plan to delve into depth and explain every concept. I will get lots of things wrong. But I am making this so I have something to reference back to. As what always happens is I learn so much, then I forget things and don’t know where to find them.

Step One - Barebones boot

First we want to make something that will just be able to boot. Something to note is that there is software that goes before the OS and its called the BIOS (Basic Input Output System). I’m 99 Percent sure that the BIOS only helps us in selecting which drive to boot from.

Where do we start

When we first boot into an OS. It has no idea what to do. But it does know where to look

There is a standardized location of something known as the boot sector.

The boot sector is located on the first sector of the disk. And it takes up 512 Bytes

If the disk it bootable. Then in byte 511 and 512 there will be 0xAA55.

What is that ^

Hexadecimals

We need a more human way to represent binary. While decimals represent numbers using 10 symbols. Hexadecimals use 16 distinct symbols, and use base 16. These are “0” - “9” to represent 0-9 and then “A”-”F” to represent values 10 - 15.

They are basically a more human friendly way to visualize and represent binary.

An 8-bit byte can represent values from 00000000 → 11111111 which can be shown as 00→FF in hexadecimal

| Hexadecimal | Decimal |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 4 |

| 5 | 5 |

| 6 | 6 |

| 7 | 7 |

| 8 | 8 |

| 9 | 9 |

| A | 10 |

| B | 11 |

| C | 12 |

| D | 13 |

| E | 14 |

| F | 15 |

Also remember its in a completely different base (16) than decimal.

so 0xAA55 would actually be equal to

$0xAA55 = (1016^3)+(1016^2)+(516^1)+(516^0)$ = 43605

Which is also

1010101001010101 Represented in binary (base 2)

Lets code

In the first three bytes we create an infinite loop. Then we fill everything between those three and 510 with zeros. Finally we populate bytes 511 and 512 with0xAA55

; Infinite loop (e9 fd ff)

loop:

jmp loop

; Fill with 510 zeros minus the size of the previous code

times 510-($-$$) db 0

; Add the indicator that it is a bootable drive

dw 0xaa55

DW = define word size (16 bits) variables.

So since we need to add 2 bytes to the end, and a byte is 8 bits. So

dw 0xaa55

dw 0xAA55

will fill the last 2 bytes with0xAA55

Something I wish to learn later. Is how is e9 fd ff an infinite loop, maybe that pattern of bites make a circuit loop?

then we need to assemble it into a .bin file

nasm -f bin barebones_boot.asm -o barebones_boot.bin

then we boot from the .bin file using qemu

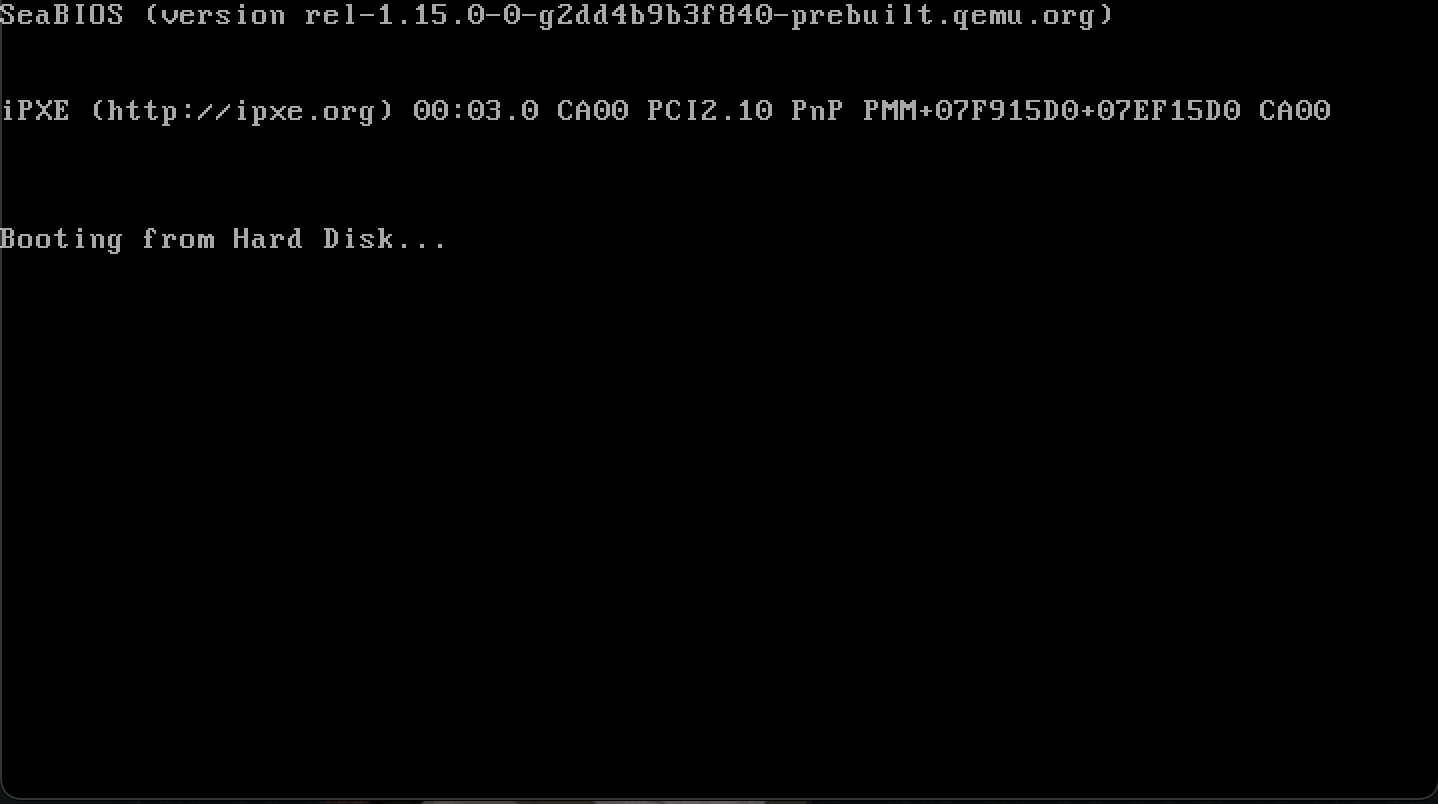

As you can see it says we are booting from the Hard Disk and just hangs in an infinite loop. Hurray!!

Printing text to screen

We will print to the screen using interrupts and CPU registers.

A register is a quickly accessible location which is available to the processor.

Interrupts and Registers

General Purpose Registers

General Purpose Registers

There are four general purpose registers

- ax - Accumulator

- bx - Base Register

- cx - Count Register

- dx - Data Register

For more info visit

Processor register - Wikipedia

What is an interrupt?

It’s basically a signal sent to the processor to stop its current process and work on a new one.

an instruction to cause an interrupt is

int 0x0A

x86 Assembly/X86 Interrupts - Wikibooks, open books for an open world

Saving data in the registers

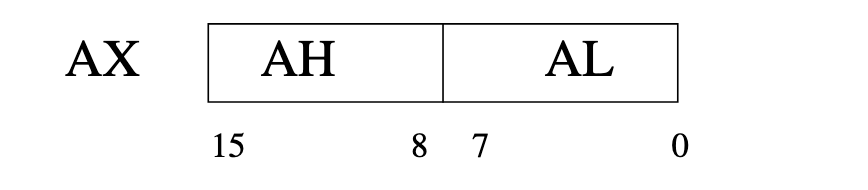

The AX register is comprised of the following.

The lower byte (8 bits) is ‘al’ and the ‘ah’ is the higher part

We will first move 0x0e into ‘ah’ which will tell the video interrupt to run the contents of ‘al’ in tty mode (teletypewriter)

mov ah, 0x0e ; tty mode

Then we will move the character ‘H’ into ‘al’.

mov al, 'H'

And finally raise the interrupt 0x10 which is the general interrupt for video services.

int 0x10

Now lets put this together and say “Hello World”

mov ah, 0x0e ; tty mode

mov al, 'H'

int 0x10

mov al, 'e'

int 0x10

mov al, 'l'

int 0x10

int 0x10 ; We already have 'l' loaded onto the 'al' part of the ax register

mov al, 'o'

int 0x10

mov al, ' '

int 0x10

mov al, 'w'

int 0x10

mov al, 'o'

int 0x10

mov al, 'r'

int 0x10

mov al, 'l'

int 0x10

mov al, 'd'

int 0x10

jmp $ ; jump to the address we are on. (will cause a loop)

; add the zeros and the space for the last two bytes to indicate this is a bootable drive

times 510 - ($-$$) db 0

dw 0xaa55

Then we do the same thing as last time, assemble the .asm into a .bin

nasm -f bin barebones_boot.asm -o barebones_boot.bin

and run it using qemu.

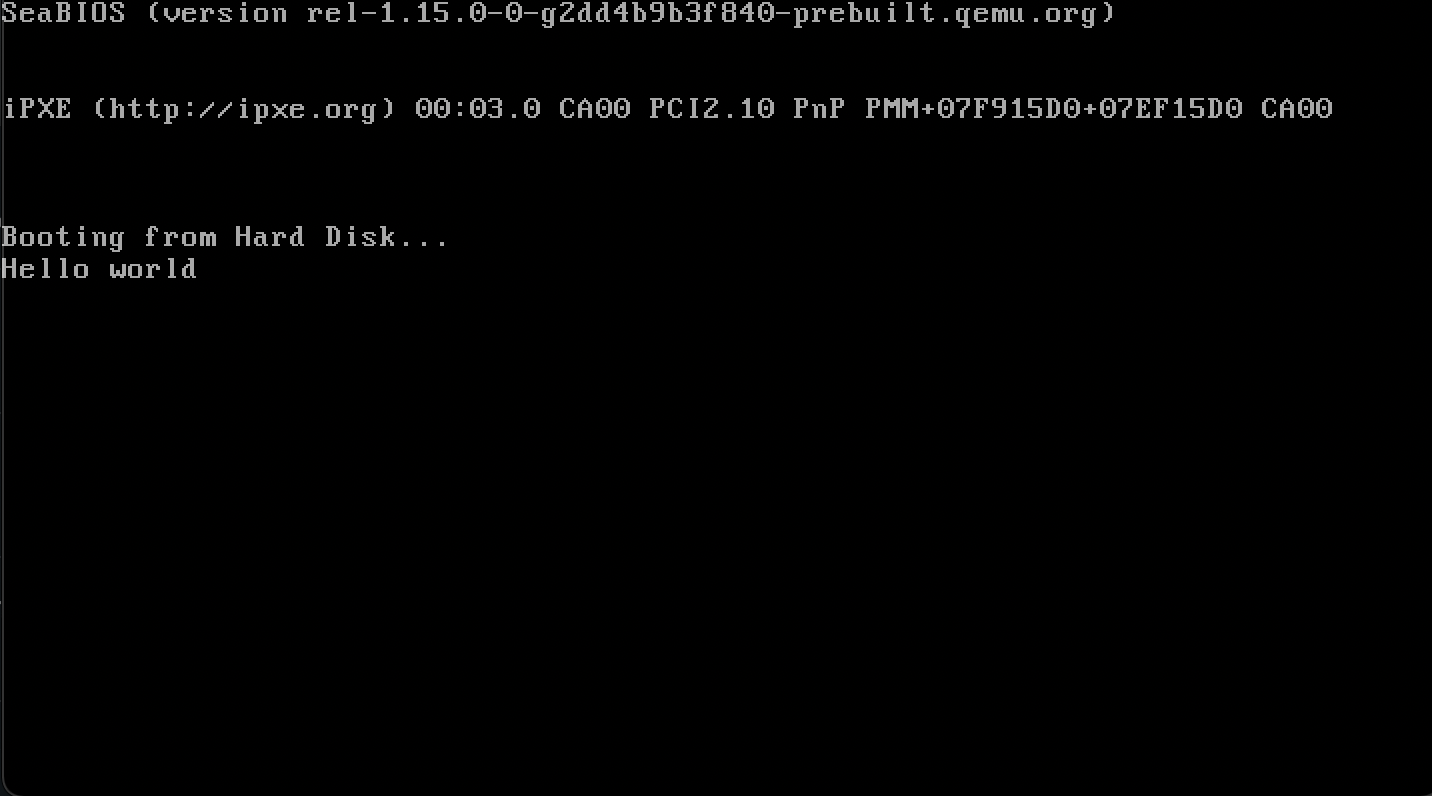

What do we see?

AND LOOK AT IT

HELLO WORLD. FROM OUR VERY OWN OS.

Boot + Memory

If you want to reference something at a certain location. You can either use the exact address of the byte. Or you can use memory offsets

Memory Offsets

If you know a base address **and you know the distance between that byte and the byte you are interested in. Then you specify the base and an offset from that address to get to the byte you are interested in.

Basically a memory offset is the distance from a byte location that you have to one you don’t have but want

In fact, previously you saw us use the jmp command. Where we used “relative jump instructions” instead of the entire memory address in bytes of where we want to go. Basically someplace that we already know rather than the whole address. This takes up less space and is often faster than jumping to the full address

Pointers

An object that stores a memory address

In commands:

mov eax,ebx

Would be the equivalent of saying:

eax = ebx

On the other hand

mov eax,[ebx]

would deference the actual value in ebx and then store that in eax

What does this mean? Well like the name “pointer” points to a certain memory location that can contain some data.

The first method

mov eax,ebx

will actually copy over a pointer to data. Which is not the data itself, instead its just telling us where it is

vs

mv eax,[ebx]

actually finds the value that ebx points to. And stores that directly in eax.

We can clarify that [ITEMHERE] will be equivalent to ITEM that ITEMHERE points to

For a deeper understanding I reccomend this resource

If you don’t understand reference vs value you can learn here

Printing from memory

Hopefully this will help you understand value vs references more

Lets introduce a new command

DB

print_this:

db "X"

DB stands for define Byte.

and

“print_this” is the label (think of it like the nickname)

So we are defining the value at the current byte we are at as the character “X” (actually its binary value)

So lets try to make it show up on screen

Method 1

mov ah, 0x0e; tty mode

mov al, "1"; For attempt 1

int 0x10; Interrupt to show it

mov al, print_this

int 0x10

jmp $

print_this:

db "X"

times 510-($-$$) db 0; fill up everything else with zeros

dw 0xAA55; indicate its a bootable sectore

The output would be

1-

or some other random garbage

This is because when we do

mov al, print_this

We save the memory address of print_this (which is a pointer) to al

Method 2

So now lets try to save the memory address value that print_this references using [print_this] instead of print_this

mov ah, 0x0e; tty mode

mov al, "2"; For attempt 2

int 0x10; Interrupt to show it

mov al, [print_this]

int 0x10

jmp $

print_this:

db "X"

times 510-($-$$) db 0; fill up everything else with zeros

dw 0xAA55; indicate its a bootable sectore

Output:

…more random garbage.

WHY?? Aren’t we saving the memory address of “X” to the al section of the “a” register?

Well, remember it’s the memory address. And do we know where the “bios” puts us? As of right now we don’t. Which means we doing the equivalent which way is north after being spun around while blindfolded.

Remember offsets? Well now we get to use them. The BIOS starts us (boot sector) at 07c00

So we would have to print the memory address of (the pointer + 07c00)

Method 3

Now we are also going to use the b register.

This is because we first need to combine print_this and 07c00 and then get the memory address of that.

and we cannot move from register a to register a

A register can’t be used as a source and destination for the same command

mov ah, 0x0e; tty mode

mov al, "3"; For attempt 3

int 0x10; Interrupt to show it

move bx, print_this; move the pointer (which in this case is the offset) to bx

add bx, 0x7c00 ; add the base address (essentially the first byte we have access to)

mov al, [bx] ; Now we get the memory address of the actuall value

int 0x10

jmp $

print_this:

db "X"

times 510-($-$$) db 0; fill up everything else with zeros

dw 0xAA55; indicate its a bootable sectore

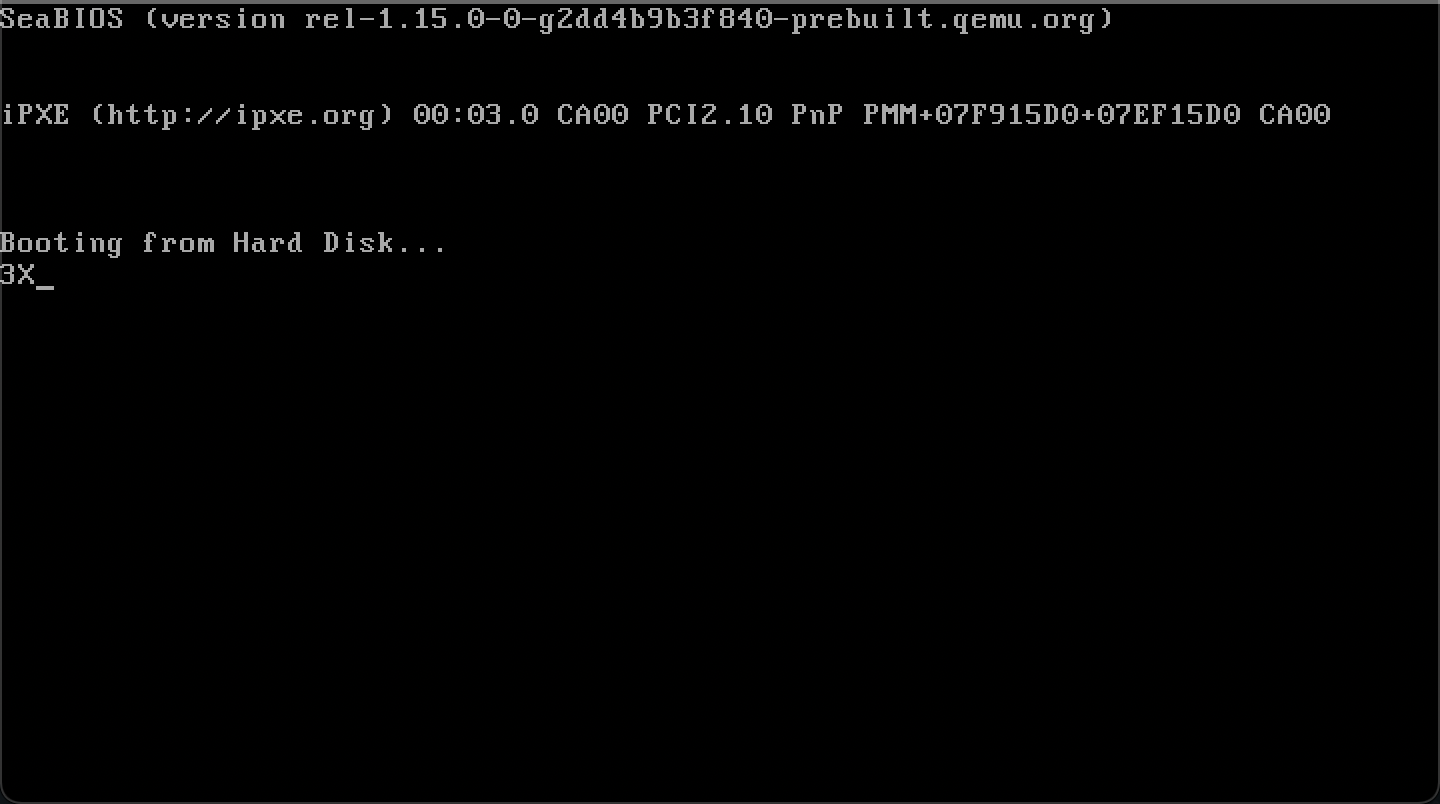

Lets run it

Yes!!! 3X. It is printing from memory now!

But this seems weird right?

Does this mean that every time we want to do anything we need to add the hex 07c00?

Well we can change it so 07c00 is the default base address for every command with:

[org 0x7c00]

Which means our final working code would be

[org 0x7c00]

mov ah, 0x0e; tty mode

mov al, "4"; For attempt 4

int 0x10; Interrupt to show it

mov al, [print_this] ; With the right base address we dont need to do anything else

int 0x10

jmp $

print_this:

db "X"

times 510-($-$$) db 0; fill up everything else with zeros

dw 0xAA55; indicate its a bootable sectore

Working with Stacks/Arrays

What is a stack?

How does the stack work in assembly language?

It is an abstract data structure that uses a Last In First Out System. Basically you put things into the stack. And then you take them out. The last item is the one that is removed, and new items are placed at the end.

Commands

BP - Base Pointer, can be used to preserve space to be able to use local values

SP - Stack Pointers, points to the current stack

IP - Instruction pointer

We can remove the latest item from the array, then we move it to the AL register. Then we use the visual interupt

mov ah, 0x0e ; Set to tty mode

Update

From this moment on I will no longer be going into such detail. As writing the explanations has taken more time and is more energy consuming than writing the code itself.

I will continue by posting and talking about my progress. What I am confused about, what I am excited about. I would say its more of a journal.

Then maybe later on I can write the entire thing in a more usable and tutorial type sense.